The ‘grand plan’ in the veggie patch

Circa 2005: from the book Tales of a Backyard Farmer

Well, as usual, nothing is going to plan in the veggie patch. It’s not that I don’t have a plan, it’s that I keep changing it! The great danger of improvising ‘on the fly’ is that you can come badly unstuck. The great benefit is that you can also break old moulds and find out new things. So the only real plan around here is less of a plan and more of a vision – I’d like to feed the family from our ‘backyard farm’.

A tour of my conventional tomato patch would have to be the definitive guide to how to stuff things up badly. It’s also the result of poor scientific method, where the basic idea is to test only one thing at a time, and by a process of replication, randomization and controls, aided by statistical analysis, state definitively that this causes that. Well, I know all that stuff, but just can’t seem to bring myself to practice it in the veggie patch. Too many self-imposed pressures to grow things and at the end of the day, eat them. If I were a real scientist on a research station, I’d have little trial plots laid out all over the place. And at the end of many days, I’d be able to push the envelope of knowledge out just that little bit more, and possibly change the way we grow our food. Meanwhile, someone would be paying me a salary and I’d be going home each night to food grown by somebody else somewhere else…

Still and all, I’m a great despiser of ‘bucket science’, and a believer (perhaps a ‘hoper’, really) that the giant intellect that got our species into this current jam will get us out of it. This means intellectual rigor needs to apply to what I do and observe and test in the garden, so at present I’m caught between the two worlds. One of the things in my favour is that our eco-system hasn’t collapsed yet (despite infestation by a particular sort of Bush!). I still have my regular day job, and so I can afford to experiment.

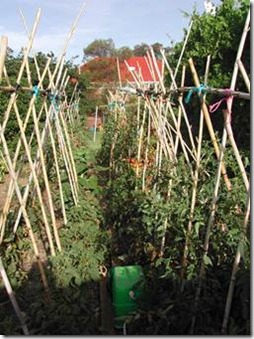

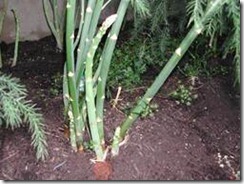

So here is where I have to own up to the chaos in the tomato patch. Fundamentally, I didn’t have the soil ready in this particular spot, although I had grown a clover green manure crop in half of it (weeds in the other half!). I cleared it up and laid new compost over the top, planted out Ox-Heart and Roma tomatoes from potted plants I’d grown from seed, then established ‘teepee’ bamboo frames to tie the growing tomato vines onto. The tomatoes are two meters high, look dreadful, and aren’t cropping at all well. What’s gone wrong?

Well, the fact is I can think of a dozen things that I could have done to wreck all the effort that went into supplying next winter’s tomato sauce. I taught one of my sons to prune, and he took out the growing shoots of a third of the plants before I realized what was going on. But that’s not it, because I pruned the rest of the hundred or so vines myself, and they’re in no better shape. Perhaps that entire pruning operation allowed disease to enter via the pruning wounds? Perhaps it’s my overhead watering, or the fact that some of the bamboo stakes were used on tomatoes last year, and carried tomato diseases into this new ground. Perhaps the weather’s been wrong, or it’s just been ‘a bad year for tomatoes’? Perhaps the seeds themselves carried forward disease?

I have no definitive proof, but I think the real answer is much simpler – I stuffed up the watering, and they died of thirst. There are two explanations competing for attention here. One is a property of the compost itself – until it’s been in the garden for some time, it is almost hydrophobic (sheds water rather than absorbs it). And I suspect as well that its water-holding capacity is much poorer than I expected – nowhere near as good as if I’d mixed it in with the clay soil underneath. Finally, while it IS compost, perhaps it is deficient in some critical minerals to be found in real soil, or is low in nitrogen or potassium or who knows what (Peter Bennett would know, I bet, but I haven’t got around to asking him). Lettuces and pumpkins and basil have thrived in it (although the basil seed took forever to germinate), while this crop of tomatoes has not.

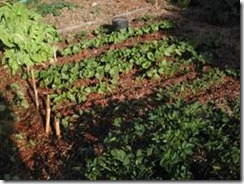

So there it is - no tomatoes from that bed and all those hours of effort. And no single explanation, a million questions and so not much learnt to caution me next time. But hey, I haven’t told you about my OTHER experiment! Perhaps I’ll be able to pull off a sauce bottling day yet… Over in the bigger garden is a patch of heirloom tomatoes (Mortgage Lifters, Yellow Pear and Rouge de Marmandes). Here I’d decided to do everything different. I grew them from seed and didn’t pot them, but planted the seedlings straight into heavy soil without compost. I’d had the broad-bean crop in this veggie plot however, and so there existed the possibility that the beans had fixed some soil nitrogen. No overhead watering for these fellows, but a weekly soak at ground level from the hose. The beds are mulched to keep the moisture there.

Instead of pruning and tying to vertical poles, I’m growing them amidst horizontal bamboo frames tied in layers to upright stakes. The bamboo poles are shiny smooth and so should not lead to abrasion wounds, and by letting the tomatoes bush out, I am avoiding pruning wounds. I may also prevent them setting a decent crop due to all that vegetative growth, and I may also have fungal disease problems due to poor air circulation, but the latter seems unlikely given the flogging they get every night from the gully winds around here! Another downer is that I’ve planted them next to some potatoes that I found sprouting in a kitchen cupboard, and decided to give a new lease of life by planting them out into the garden. According to the books on companion planting tomatoes and potatoes together do badly. But who does badly, the potatoes, the tomatoes, or both? Perhaps I’ll find that out too? Perhaps I’ll just wind up even more confused…

So here I am again, still risking the possibility of store-bought tomato sauce for lack of care and rigor, but having fun. This whole veggie patch is an experiment really, and they’ll carry me out of here in a pine box before I understand it all. But one of the few things that I have learnt so far is that there is no need to understand all the relationships in an organic garden. Old Mother Nature has her mysterious ways, and it’s not my job to oversee her machinations.

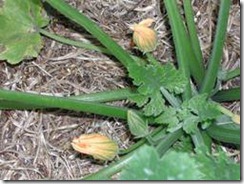

Besides, right down the back of the garden is Tomato Experiment #3, where I’ve got all those Bell Star tomatoes that I’m growing on deep straw mulch with no staking or pruning at all. Perhaps there’s still a chance for winter pasta? If not, the pumpkins are doing well, or will they be adversely affected by more of those rogue potatoes?