Broccoli is the mainstay of our vegetable dishes throughout winter, and so saving broccoli seed for the following year is an important chore each summer. While this is a simple enough task, plants saved for seed production do take up extra space in the garden through springtime when the major summer crops are all jostling for garden space. All one needs to do is to leave the best broccoli plants unpicked, as it is the immature flower head itself that we have been eating. Two things happen as broccoli goes to seed; small yellow flowers break out all over the broccoli head, then the head itself shoots up to several metres tall, attracting bees and other pollinators with a rich supply of nectar.

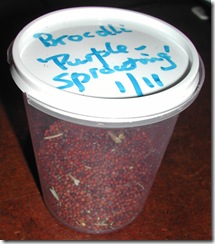

There are two styles of broccoli plant; those that produce a single large head then shut down, and ‘sprouting broccoli’ that produces many small florets that reshoot over and over again after picking. It is the latter type that we favour, as they produce for longer and the small heads are easy to harvest and to prepare. After experimenting with various varieties, we have settled on ‘purple sprouting broccoli’ as best suited to our soil type, climate and palate.

After flowering and pollination finish, broccoli – like most members of the brassica family – form long dried pods resembling upright miniature peas called ‘siliques’ that house about a dozen individual seeds. These are arrayed along the stalks that stand above the original plant. Once the seeds inside the siliques have turned from green to brown, cut off the stalks and lay them on the ground or hang them by their heels in the shed to dry further.

After flowering and pollination finish, broccoli – like most members of the brassica family – form long dried pods resembling upright miniature peas called ‘siliques’ that house about a dozen individual seeds. These are arrayed along the stalks that stand above the original plant. Once the seeds inside the siliques have turned from green to brown, cut off the stalks and lay them on the ground or hang them by their heels in the shed to dry further. When the whole shoot is no longer green but hard and woody, place the heads over a bucket and simply don your heavy-duty leather gardening gloves and rub the seed heads between your two hands to release the small spherical seeds from the siliques. These will fall to the bottom of the bucket. The dry stalks are picked out and returned to the garden as mulch, or thrown onto the shredding heap.

When the whole shoot is no longer green but hard and woody, place the heads over a bucket and simply don your heavy-duty leather gardening gloves and rub the seed heads between your two hands to release the small spherical seeds from the siliques. These will fall to the bottom of the bucket. The dry stalks are picked out and returned to the garden as mulch, or thrown onto the shredding heap.

Pour the seed into a small shallow dish, then blow gently on it (while standing outside in the breeze and gently swirling the dish) to remove all the small bits of dried twigs and rubbish. Put the cleaned seed into a jar, label it, then add it to your seed collection.